Safe from scandal

Regular checks along the production chain can prevent meat scandals, explains Alexander Flath, division manager sales at SGS Germany.

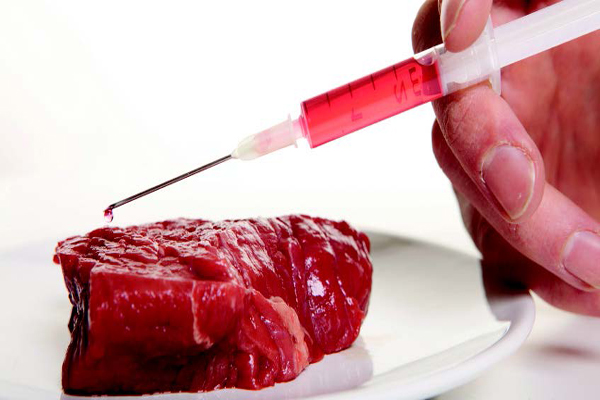

Rotten meat, resistant germs and incorrect product labelling; time and again the media disseminates negative headlines referring to ‘meat scandals’ with consequences for both the industry and retailers. The discovery of horse DNA in frozen foods in 2013 presented new challenges to the producers and processors of meat products across Europe. What is the exact origin of the meat? Who processed it and how was it processed before it reached manufacturers and retailers? Audits and independent controls can provide reliable answers to these questions.

Whether it is mad cow disease, adulterated feed fat or the horsemeat scandal, there have been repeated public discussions on alleged misconduct in the production and processing of meat products. Negative media reports not only reduce consumer willingness to buy, but also fuel public and political demands for comprehensive quality control throughout the entire production chain of food of animal origin.

A recent example, referred to as the horsemeat scandal, made headlines in Europe in early 2013. Admixtures of horsemeat were discovered in various beef products, such as lasagne and bolognese sauce, which did not list these ingredients on their packaging. The result was angry consumers, product recalls and reputation damage, even in the case of well known brands. Naturally, this revived the issue of the seamless international traceability of meat. What caused particular uncertainty among consumers and preoccupied the press and politicians was the difficulty in tracing delivery routes that pass through numerous suppliers, distributors and processors across several EU country borders.

The aftermath of this deceptive labelling can be seen today in the EU’s significant tightening of its rules for product declarations. Starting in April 2015, it will be mandatory to specify the origin of pre-packaged meat from pork, poultry, goats and sheep. Currently, a change in the law is being considered in which even the origin of processed meat as an ingredient will need to be disclosed on the package of processed foods such as lasagne, soups or sausages. In the future, the meat industry may have to become accustomed to undergoing regular mandatory DNA testing that will expose any false declarations.

Beef labelling: the legacy of BSE

The far reaching consequences that can result from a meat scandal, and the criticism directed at players in the meat market, can be illustrated by the BSE crisis occurring around the turn of the millennium. At its peak, this crisis involved more than 1,300 diseased breeding cattle in the UK and over 120 BSE cases in Germany.

It was not until the emergence of the cattle disease and the public debate about its causes that proper guidelines for guaranteeing the origins of beef were formulated in all European countries. The regulation by the Federal Agency for Agriculture and Food (BLE) that applies to beef labelling has been in effect in Germany since 2000. Since the introduction of this regulation, each market participant in the Federal Republic is obliged to disclose the required information pertaining to the origin of the processed beef, from the slaughterhouse to the shop, using an appropriate label.

Using audits to identify errors

With regard to the presence of horsemeat in ready made products, it should be noted that in many EU countries it is much more common to slaughter and consume horses at the end of their lifespan than it is in Germany. A problem arises only when companies do not realize that a distinct separation of flow is required when different meats are processed, and that therefore, an intermediate cleaning of the processing equipment is necessary. A meat cutting plant that deals with both cattle and horses but does not perform sufficient intermediate cleaning runs the risk that the DNA of unwanted types of meat will be detected in analyses.

This process error is relatively easy to discover in the context of neutral supplier audits; however, a deliberate mixing of meat or a purposely misleading label is much more difficult to detect. There is an urgent need, both nationally and internationally, to ensure a transparent, traceable product chain starting from animal feed to animal husbandry, slaughtering and processing, through to the retail market – a system already implemented for many meat products produced in Germany.

Applying a holistic concept of control

For this type of fundamental review to be successful, it must be sequentially performed along the entire value chain. This means that the birthing, fattening and slaughter companies must be routinely controlled along with everyone involved in the processing operation during production – regardless of location or continent.

It is essential to establish clear rules to implement an effective, practical, credible and feasible control concept. The farms that supply meat products to the shelves of grocery stores need to show responsibility. Each processing plant involved in the production process should:

- Analyse its supplier relationships

- Complete all information on the product’s life course and provide this from the birth of the animal

- Delegate responsibility to the next supplier through the use of supply contracts.

For these purposes, SGS provides simple web-based database solutions in which each company worldwide can register with their address and other information. These databases are password protected and only visible to the owners of the respective control concept.

Testing procedure

When all companies in the supply chain have been clearly identified, a risk oriented inventory is taken for each separate source. The basis of the overall control concept is always effective self monitoring implemented in the individual companies of the supply chain. The more the concept of self monitoring is present and put into practice, the lower the frequency of testing carried out by SGS. A key factor is transparent supply routes with clear product flows, if possible through the use of automatic systems.

Reviews must also take into account by-products and the losses incurred, and they must be plausibly verified. Other potential influences, such as the simultaneous slaughter and cutting of other types of animals on the same slaughtering or cutting belt, also play a role in the risk assessment.

System and sample audits

As a rule, there is first a preannounced system audit to achieve an overview of the current situation. Based on the results of this survey, the extent of testing unannounced random sample audits is determined. A maximum of one day is the time taken for a system audit and the time for an unannounced random sample audit is estimated at half a day. Unannounced random sample audits usually review Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), based on a Europe-wide quality management policy and accounting for the flow of goods.

Audit results are substantiated by taking random samples of each end product at every company in the supply chain. These are then analysed in SGS laboratories for specific parameters. These parameters are determined in a flexible manner so that it is possible to test alternately for pathogenic germs, unwanted substances such as aflatoxins, heavy metals, dioxins, carcinogenic organochlorine compounds and antibiotic growth enhancers. DNA analyses are also performed regularly to determine species. In the future, DNA analyses of goat meat may also be available for meat supplied by numerous non-EU countries. Analyses for dog and cat meat percentages could also be conceivable for supplies from other regions.

SGS has a worldwide network of laboratories where these examinations can be conducted in the countries of origin. The analyses comply with current EU requirements. The laboratories perform calibrations in concert with one another, so that the results of the analyses are comparable and meaningful in all countries.

Finally, it is important to note that no preventative measure is 100 per cent effective in protecting against criminal activity or deliberate fraud in the mislabelling of meat. However, if the product chain is documented in detail and traceable, the potential ‘suspects’ can be identified more quickly and further action can promptly be taken. This transparency makes it possible to deal with meat scandals quicker and in a more targeted manner.